Summary: A user story is an informal, general explanation of a software feature written from the perspective of the end user. Its purpose is to articulate how a software feature will provide value to the customer.

It's tempting to think that user stories are, simply put, software system requirements. But they're not.

A key component of agile software development is putting people first, and a user story puts end users at the center of the conversation. These stories use non-technical language to provide context for the development team and their efforts. After reading a user story, the team knows why they are building, what they're building, and what value it creates.

User stories are one of the core components of an agile program. They help provide a user-focused framework for daily work — which drives collaboration, creativity, and a better product overall.

What are agile user stories?

A user story is the smallest unit of work in an agile framework. It’s an end goal, not a feature, expressed from the software user’s perspective.

A user story is an informal, general explanation of a software feature written from the perspective of the end user or customer.

The purpose of a user story is to articulate how a piece of work will deliver a particular value back to the customer. Note that "customers" don't have to be external end users in the traditional sense, they can also be internal customers or colleagues within your organization who depend on your team.

User stories are a few sentences in simple language that outline the desired outcome. They don't go into detail. Requirements are added later, once agreed upon by the team.

Stories fit neatly into agile frameworks like scrum and kanban. In scrum, user stories are added to sprints and “burned down” over the duration of the sprint. Kanban teams pull user stories into their backlog and run them through their workflow. It’s this work on user stories that help scrum teams get better at estimation and sprint planning, leading to more accurate forecasting and greater agility. Thanks to stories, kanban teams learn how to manage work-in-progress (WIP) and can further refine their workflows.

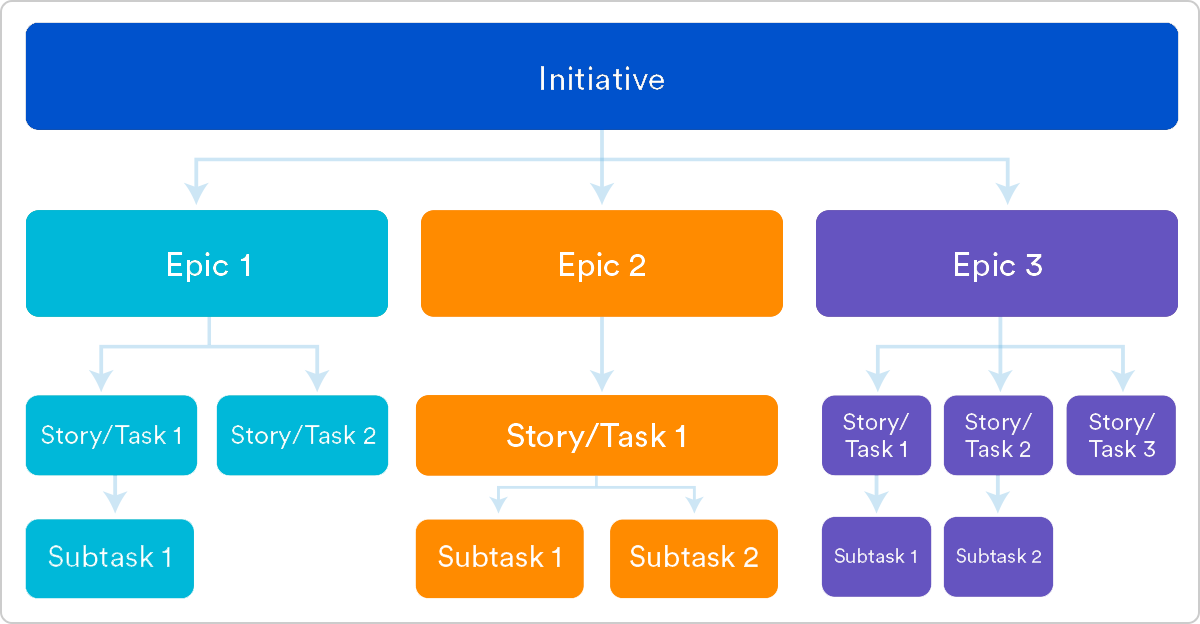

User stories are also the building blocks of larger agile frameworks like epics and initiatives. Epics are large work items broken down into a set of stories, and multiple epics comprise an initiative. These larger structures ensure that the day-to-day work of the development team (on stores) contributes to the organizational goals built into epics and initiatives.

Why create user stories?

For development teams new to agile, user stories sometimes seem like an added step. Why not just break the big project (the epic) into a series of steps and get on with it? But stories give the team important context and associate tasks with the value those tasks bring.

User stories serve a number of key benefits:

- Stories keep the focus on the user. A to-do list keeps the team focused on tasks that need to be checked off, but a collection of stories keeps the team focused on solving problems for real users.

- Stories enable collaboration. With the end goal defined, the team can work together to decide how best to serve the user and meet that goal.

- Stories drive creative solutions. Stories encourage the team to think critically and creatively about how to best solve for an end goal.

- Stories create momentum. With each passing story, the development team enjoys a small challenge and a small win, driving momentum.

Working with user stories

Once a story has been written, it’s time to integrate it into your workflow. Generally a story is written by the product owner, product manager, or program manager and submitted for review.

During a sprint or iteration planning meeting, the team decides what stories they’ll tackle that sprint. Teams now discuss the requirements and functionality that each user story requires. This is an opportunity to get technical and creative in the team’s implementation of the story. Once agreed upon, these requirements are added to the story.

Another common step in this meeting is to score the stories based on their complexity or time to completion. Teams use t-shirt sizes, the Fibonacci sequence, or planning poker to make proper estimations. A story should be sized to complete in one sprint, so as the team specs each story, they make sure to break up stories that will go over that completion horizon.

How to write user stories

Consider the following when writing user stories:

- Definition of “done” — The story is generally “done” when the user can complete the outlined task, but make sure to define what that is.

- Outline subtasks or tasks — Decide which specific steps need to be completed and who is responsible for each of them.

- User personas — For whom? If there are multiple end users, consider making multiple stories.

- Ordered Steps — Write a story for each step in a larger process.

- Listen to feedback — Talk to your users and capture the problem or need in their words. No need to guess at stories when you can source them from your customers.

- Time — Time is a touchy subject. Many development teams avoid discussions of time altogether, relying instead on their estimation frameworks. Since stories should be completable in one sprint, stories that might take weeks or months to complete should be broken up into smaller stories or should be considered their own epic.

Once the user stories are clearly defined, make sure they are visible for the entire team.

User story template and examples

User stories are often expressed in a simple sentence, structured as follows:

“As a [persona], I [want to], [so that].”

Breaking this down:

- "As a [persona]": Who are we building this for? We’re not just after a job title, we’re after the persona of the person. Max. Our team should have a shared understanding of who Max is. We’ve hopefully interviewed plenty of Max’s. We understand how that person works, how they think and what they feel. We have empathy for Max.

- “Wants to”: Here we’re describing their intent — not the features they use. What is it they’re actually trying to achieve? This statement should be implementation free — if you’re describing any part of the UI and not what the user goal is you're missing the point.

- “So that”: how does their immediate desire to do something this fit into their bigger picture? What’s the overall benefit they’re trying to achieve? What is the big problem that needs solving?

For example, user stories might look like:

- As Max, I want to invite my friends, so we can enjoy this service together.

- As Sascha, I want to organize my work, so I can feel more in control.

- As a manager, I want to be able to understand my colleagues progress, so I can better report our sucess and failures.

This structure is not required, but it is helpful for defining done. When that persona can capture their desired value, then the story is complete. We encourage teams to define their own structure, and then to stick to it.

Getting started with agile user stories

User stories describe the why and the what behind the day-to-day work of development team members, often expressed as persona + need + purpose. Understanding their role as the source of truth for what your team is delivering, but also why, is key to a smooth process.

Start by evaluating the next, or most pressing, large project (e.g. an epic). Break it down into smaller user stories, and work with the development team for refinement. Once your stories are out in the wild where the whole team can see them, you’re ready to get to work.

.jpg?cdnVersion=1881)